If Nassim Taleb were a VC

The Book of Genesis as a story in dialogue - derivatives pricing applied to venture - uncertainty-maxxing - and of course, via negativa

If Taleb, or one of his lackeys, ran an early stage venture fund - let’s call it TalebFund - what would it invest in? How would he construct a portfolio? What would a fragile venture fund look like and how would he avoid building it?

Instead of narrative-maxxing…

One of the best explanations I’ve heard about the Book of Genesis is that it’s a narrative intentionally in dialogue with other first millennium BC cultures. The Hebrew authors tell themselves their story, with God crafting Adam and Eve as the pinnacle of His creation, Imago Dei. This is a fundamentally different worldview to, say, Sumerian creation myths where mankind is born from the violent clash of the gods (Enuma Elish) or created to serve them as underlings (The Song of the Hoe, Enki and Ninmah).

This has, all these years later, been the best example for me to understand how the stories we tell ourselves shape our understanding of the world. The world is so complex and there’s so much randomness, that the most Lindy way to separate out the signal is to pattern it into symbols and rules.

In venture, this is industry protocol.

As investors, we pattern match to tech inflections (internet, mobile, crypto, AI), to markets (“the XYZ for India”), and we pattern match to founder stories. Moments like Masa Son telling the audience he was investing in Jack Ma because he loved Jack’s “strong eyes and he had no business plan”, or SBF gaming in his pitch meeting have become canon.

“As companies rise in prominence, their narratives become more solidified. Doubters are silenced as investor dollars flow in (which people equate to success) and echo chambers ring louder and louder, reinforcing consensus with little room for doubt or nuance.”

The more successful an investor gets, the more they value their time. They’ve seen great founders before, and so have less tolerance for those who don’t fit those patterns. Successful investors have more to lose if they miss the next big thing, and the mathematics of their now-larger funds means they must take bigger swings and must look for bigger upside. What worked before is no longer enough: large funds and a post-success mentality mandate finding bigger and bigger stories.

It’s psychologically hard for a fund to stay small, underwriting companies to “$2bn returns a fund”, and there are only so many non-obvious markets and talent pools a small GP team can find. Instead consensus great founders or exciting markets are justified explicitly by underwriting outcomes to the hundreds of billions, and implicitly by the self-confidence and branding that being early to a Very Big Story brings.1

“The last two decades have awarded sourcing the best deals, and winning access to them, so big funds hired and trained for this. This dynamic has created a generation of investors who are excellent networkers and salespeople, but fairly limited pickers.”

The problem is not only in the mechanics of scaling, but in the narrative fallacy we VCs are so prone to. We are perhaps over-quick to credit our success to better pattern-matching than others so, once that success comes, we begin to lose the critical examination and paranoia that brought it there in the first place. We think we’re hydrated from drinking our own Kool-aid, but actually it’s the water that did it.

“The way to avoid the ills of the narrative fallacy is to favor experimentation over storytelling, experience over history, and clinical knowledge over theories… I do not forbid myself from using the word cause, but the causes I discuss are either bold speculations (presented as such) or the result of experiments, not stories.”

Taleb “The Black Swan”, page 84.

As with our Genesis example, stories about founders or markets can be powerful mechanisms to separate signal from noise in a chaotic world. But, as with the Genesis example, it’s far more helpful if these stories are in dialogue. Submitting them to comparison with other stories, seeing them in the context of the zeitgeist, is necessary for critical examination. What are other smart investors seeing? What do I see that they don’t?

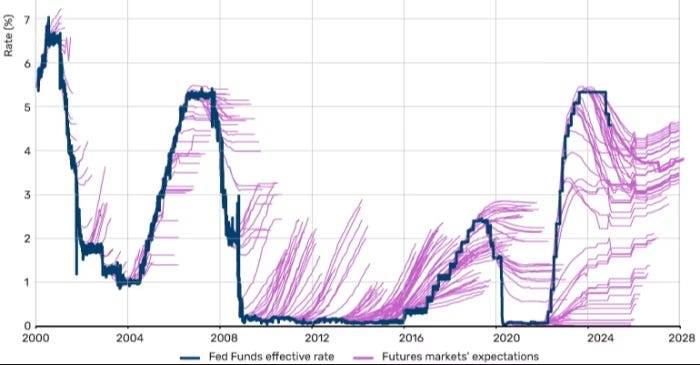

The reality is that, partly because of this narrative fallacy, prediction is really, really hard. Even in the massively institutionalised world of options pricing, people are usually wrong.2

Since it was such a large part of Fooled By Randomness and Black Swan and such a common pitfall in venture, I imagine our hunger for stories and the drifting away from experimentation over time is the first thing TalebFund would try mitigate. One way to do this is by disassociating somewhat from the ‘company building’ part, by trying to make venture behave like some other asset convex class, perhaps derivatives?

… Taleb would convexity-maxx

My colleague Yavuzhan recently wrote an essay transposing derivative pricing to venture. If you’ve not read it yet, stop and do so, it’s required reading (and a more technical explanation) for this one. To quote him:

“Both out-the-money call options and early-stage investments rely on trading fat tails, extreme events of low probability. The investor knows that the chances of a payout are low, but the chances of an extreme payout are not as slim as many other market participants (or a normal probability distribution in the case of call options) would think.”

Venture funds are inherently antifragile, using no leverage and being - in this analogy - a basket of call options. As with any options strategy - there’s often a trade-off between convexity, certainty, and cost. The key to options management then is to construct a portfolio that expresses a view in an efficient (low cost), yet powerful (high convexity) way.

And so we get to the crux of this piece: since prediction is hard and the incentive set in venture is to look for stories, the Talebian approach is to focus on convexity, not certainty. Said otherwise: on payoff of outcome, not the probability of outcome.

“We can have a clear idea of the consequences of an event, even if we do not know how likely it is to occur. I don’t know the odds of an earthquake, but I can imagine how San Francisco might be affected by one. This idea that in order to make a decision you need to focus on the consequences (which you can know) rather than the probability (which you can’t know) is the central idea of uncertainty.”

Taleb “The Black Swan”, page 211.

In most cases, the most impactful lever an investor has to mitigate risk (and improve the upside) at a portfolio level is their entry prices. Convexity is increased by lowering the cost per unit trial (price), and by funding far-out-there ideas, which we’ll get to later.

For instance, take Instacart at IPO, generally considered a winner. Firstly, you’ll see it was only a winner for the early investors. Yet even among the early ones there are key differences. YC was too diversified for their $75k ticket ($8.5m return) to matter much at the fund level, Sequoia - who bought in at the same price but after a year of de-risking - captured the lion’s share of the alpha, and anyone who came after a16z lost money.

A $100m fund investing in 100 companies at an average of $100m valuation, facing 66% dilution and with the best outcome being $10bn barely returns the fund (1.3x, gross). In a world where the the Nasdaq has done around 15% annualised over the last decade, 5x TVPI is table stakes for same vintage funds.3

Most venture deals - even the Instacart-sized ones - don’t yield this for most investors. The lads at Level Ventures did a great job unpacking the comparative return profile of expensive seed rounds:

“[T]he trend is clear: seed (& pre-seed) deals with a below $20M post-money have (on average) 280% the probability of producing a 50x+ hit as compared to their higher valued counterparts.

Why is this the case? Certainly, a lower entry valuation means that returning 50x+ is mathematically easier to do (by definition). But perhaps there’s something more. I hypothesize it’s a confluence of several factors - capital efficiency (less capital may require more scrappiness and stronger core focus), team incentives (less money could mean that equity incentivization plays a larger role, aligning the team toward a shared mission), dynamics of the business (if it takes more capital to get up and going, it may take more to continue scaling, which could dilute investors), and perhaps ego (raising money is a means to an end).”

It’s easier to tell yourself that you’re not getting adversely selected when you’re getting into hot rounds, and every GP thinks the deal they pay up for will be the one that returns the fund. This is of course fine, so long as you’re right (or, in LP discussions, you have a convincing rationale). But when every company in the fund (or the majority) are higher entries, for pedigreed teams, building in consensus markets, you’ve got to question your edge. Whether you’re paying up, meeting founders super early, or are the only bid at the table, what is it that you are seeing that other’s aren’t?

“The earlier you can source, pick, and win a great founder over, the better your returns will be. But everyone else is trying to do the same. Usually you have to see something they don’t in either the product, market, or person... Either way, the best seed investors don’t really compete for deals.”

The most common objection to our hypothetical TalebFund’s approach would be that it’s “adverse selection”. That Taleb would be fishing in competitive pools, where others are seeing the better deals earlier, and so by filtering so aggressively on price he would be getting everyone else’s leftovers.

Perhaps this is true to an extent. Any well-covered talent pool (Stanford grads, venture scouts, early Stripe employees, people with ‘Stealth’ in their LinkedIn bios) would be hard for him, a 64 year old retired quant, to justify having an edge in. Same for most hot narratives (if he first discovered the thesis in a podcast or article, it’s probably off limits).

And so he’d look to the fringes, to areas harder for other venture investors to price effectively. These could be areas either where the narrative lags (say, African industrials, or Indian biotech), or where the founder talent is outside the LinkedIn-scan-purview of most venture funds (say, construction).

His goal here would not be trend-level conviction. Rather, it’d be to lose a little bit of money often, being too early investing in things that are massively Big If True.4 Jerry Neumann articulated this really well in his recent letter, I recommend reading the whole thing.

“The idea of Knightian Uncertainty, that some things, especially in entrepreneurship, you can’t predict and can’t even assign a probability distribution to, banged into another idea that had been floating around in my head: Taleb had argued in his just-published The Black Swan that unpredictable events drove fat-tailed losses in finance. If every problem is an opportunity, I figured you could take the other side of that bet. If it were true that financiers on the whole make profits slowly for years and then, every once in a while, lose them all and more in sudden “black swan” events, then there should be some way to lose money slowly for years and then suddenly make it all back and more. Black swans are awful in traditional finance, but they’re the winning lottery ticket in venture capital.

Uncertainty around startups and their power-law outcomes were exactly that reverse bet. My theory was that the power-law returns resulted from the uncertainty. You have to invest in startups where there was uncertainty around some key aspect if you wanted to find the occasional black swan. I’d think and write a lot about this later on, but I decided to take a leap and implement it immediately. It became the centerpiece of my investing strategy…

When I explained why I made certain investment decisions, people took it as fluff and decided I was just lucky. In reality, I researched what was knowable. If it was all knowable, I said no. If something was manifestly unknowable, I embraced it. And, of course, I was lucky.”

Resignation Letter, 2024

What Jerry is talking about is not adverse selection. It’s the second way of increasing convexity: funding the far-out-there-ideas, the Big If True ones. It’s one of the reasons I love the general venture zeitgeist around deep tech right now. If crazy bets like underwater energy storage, transformer-specialised chips, or tiny semi fabs succeed, there’s less chance they’re mid-market outcomes. If venture is supposed to be the riskiest asset class, let it be the riskiest asset class.

In conclusion, it’s easier to know what it’s not

I doubt it’d be this centralised, top down thing, filling a process with agents pushing their career forward with every deal they can get through their superiors and their check-list style IC meetings. I imagine TalebFund would have one, maybe two or three key decision makers, all with a large chunk of their own money and reputation on the line, and they’d be on the ground speaking to founders themselves.

Small, pre-success teams, with their skin in the game, fighting an up-hill battle against their lack of brand flywheel, have a lot more to lose if their early funds don’t perform. In big funds, the responsibility for bad decisions is distributed across the many partners, the brand, and the analysts. In small funds, it’s just you. You mess up and you’ve got nothing to fall back on - knowing this lends you a certain paranoia, an urgency, which isn’t as often found in the larger funds. Small funds are similar in some sense to Taleb’s ugly doctor.

Further, imagine a man taking an urgent, can’t-miss flight home, which he booked for only $400 several weeks back. Imagine he finds out this plane is delayed - broken in fact - and he has to wait three days for repairs, much to his chagrin and angst. The time pressure he is under forces his hand and he forks out $4000 for a same-day ticket with a different airline, a painful 10x on the price he thought he’d gotten. Because of the 10+2 year lifetime of most funds, large funds face increasing deployment pressure like this unfortunate chap. Having too much money for your opportunity set fragilises a fund, so I suspect TalebFund would be intentionally size constrained.5

But what he would do, I’m much less sure.

I’m particularly curious about whether he’d be in the camp of maximising the surface area of exposure (ie the number of paths covered to benefit from potential positive Black Swan events), which I think means diversified? Or whether it’d be a case of “bet heavy when you have edge”. Barbelling the two approaches is hard, given nearly no venture asset is robust enough for capital preservation.

If you’ve thought about this, please reach out. Thanks to my loving wife, Yavuzhan, Cez, JT, Nikhil, Dan, for thoughts and chats going in to this piece.

“I like the personal story of betting on out of the money ideas and people that are misunderstood and underestimated. Allocating them [sic] justifies for myself egotistically what I do, and I also think it’s capitalism at its best.”

On Value Seed Investing, 2024

I’m not advocating for a mid-market strategy. This is venture, of course you’re shooting for $100bn. My point is simply that we too often, using this logic, err toward justifying paying up for a portfolio of expensive options, reducing its overall convexity. See footnote 4 as well.

True, on a spectrum, some folk are better at it than others - they have some unique insights that lend them conviction in a company or founder which others lack. Usually this is the result of having gone really, really deep on something for many years (for example, Hummingbird and nonlinear founders, Compound and market inflection points, Multicoin and alternative blockchains)

With the caveat that this applies for the past 10 years vintage. As for next 10 years, things might change and I’m not sure we should expect 15% consistently from public indexes.

I use Big If True here to contrast with Small If True: using low entries to justify targeting the mid-market outcomes. Venture is obviously a power law game, and you’ve got to take huge swings, but this is a false trade-off; Big If True thinking doesn’t necessitate high entry prices.

Most big funds use a similar-sounding pitch: “unlimited upside, therefore you can index high probability deals at seed for optionality to deploy large checks at Series As”. Most big funds are (correctly) going after Big If True because of their deployment constraints and their (unique) ability to capture price alpha comes at A+ not pre-seed.

Most small, pre-seed funds should also go after Big If True outcomes. In choosing between the pricey repeat SaaS founder building vertical AI, and a moonshot space bet in a market that’s risky and big and unknowable - with both at the same price - it’s probably more convex to choose the space bet. But the probability of success or its magnitude is not as easily recognisable on Day 1, so entry price is the biggest lever an investor has for convexity, not the market.

Admittedly the “next big thing looks like a toy” line of thinking is hard to square with this…

I lifted this example straight from Anti-fragile.

To quote a friend, quoting a quote: “All models are wrong, some are useful”, I have to imagine if this fund ever did in fact launch it wouldn’t look like how we’re thinking it would, but in this case the exercise is useful”.