An LP's Guide to Venture Funds (Part 2) - Deep Tech and Hard Stuff

The unbundling of the Last Supper - "It's a big club, and you ain't in it" - the theme changes but the grift doesn't - why we're buying consensus - and robots

This is the second in a series of articles helping LPs explore the venture landscape. Here’s the first, the Unbundling. I also wrote a primer on Chinese semiconductors a couple years back with Lillian Li at Baillie Gifford. It is a decent adjacent on this as it covers both geopolitics on deep tech, and the technical complexity of some of these industries.

Executive Summary

What’s the point of this article? To make the case that aping in to deep tech startups through smart venture managers is a pretty good idea.

What’s the TLDR? Deep tech has massive tailwinds and an investment bottleneck at seed due to the high technical and market barriers for GPs. This favours early stage, highly concentrated GPs.

Why deep tech and why now? There’s more funding, the hardware and software primitives are much cheaper and rapidly improving, talent is (slowly) being trained, and there’s geopolitical and demographic necessity.

Actionably, what can I take from this? There’s a framing of the landscape at the end, along with several of our takes on what to look for and how to find great pickers. We try to be open minded on where to look, and have found robotics and life science to be fairly good ponds to fish in!

An introduction to what we’re buying

At this point it’s pretty much consensus.

Last year Packy wrote about this. So did Paddy. So did Evan, Eli, Marc, Noah, and Ezra. Turner is posting defence memes. a16z started an American Dynamism practice. Anduril’s last raise brought them to household fame. Village Global started a podcast. Mike even wrote a great piece on the whole aping in phenomenon.

The narrative arc of innovation goes like this: In a bygone era we had Bell Labs and Fairchild and all of venture was hardware. Then we had this Internet driven boom, software ate the world, and we fell in love with this zero-marginal-cost-Brian-Arthur world. But there’s been some stagnation and now it’s time to build and we’ll all follow Thiel’s charge.

Only it’s not this easy. Deep tech (which I’ve defined in the footnotes)1 is hard to build and value, carrying science risk, market risk, engineering risk, and scaling risk. Most investors are biased against the “capex dilution of hardware”. The vast bulk of VCs have grown up in a software-is-eating-the-world mindset and this doesn’t go away with a couple blog posts. It takes years to build the network, understand the founders, and get familiar with the tech. “It’s a big club, and you ain’t in it” said the late comedian George Carlin.

Our thesis is that:

The best deep tech GPs will see better opportunities now than they did five years ago,

These opportunities will be missed by most outsider investors, and

Because of way tech risk is mitigated, the biggest bottleneck to allocation exists at seed

I’m hoping, through this article, to help a couple LPs frame whether they want generalist or specialist exposure, which segments of deep tech they want exposure to, and most importantly, how they can find a guide to help them navigate this market.

Why Deep Tech and Why Now?

Historically, deep tech has received 7-10% of global venture. The ±120 sector unicorns minted from this have produced ±$463bn in aggregate value with an rough time to IPO of 5-10 years. CB Insights has it that there are roughly 1200 VC-backed unicorns in total from the last 20 years and, depending what you consider "deep tech", anywhere from 120 to 350 of these unicorns fall under that bucket. So, butchering nuance, 7-10% of venture has been responsible for 10-30% of the unicorns.2

A meagre ten years prior, most companies were component-based and unscalable. The deep tech landscape was was similar to orthodox biotech - VCs would take large stakes of high-failure-rate businesses and billion-dollar exits were incredibly rare. Dilution was high, and so only larger firms and CVCs would take these bets.

Today, it’s quite different. The VC side has unbundled into all sorts of niche firms who act as signal for larger multi-stage GPs, and who partner at nearly every stage of technology risk level. More founders are now prioritising scalability, bringing the average age in the room down by a near decade, and innovating as much on the business model as on the tech. There’s been more investment in platforms or primitives (vs components), and we’ve started to see emerging billion dollar companies and mafias (Tesla, Palantir, SpaceX, OpenAI) which re-invest talent and money back into the network.3

There are myriad tailwinds, discussed below, but the founder profile and talent recycling are the most important to track. There’s still a severe talent shortage - both executive and technical. It feels somehow like there are more GPs interested in deep tech than founders. There’s also a shedload more money than usual being yeeted in, so GPs have to be extra careful not to pay the bid up valuations for hot deals.

Tailwinds (or Everything, Everywhere, All At Once)

All tailwinds result in two net outcomes for companies. One, a lower cost of capital. Two, better unit economics.

Lower cost of capital

Increase in private and state funding (stemming from geopolitical & demographic necessity)4

De-risked entrepreneurial path - more founders and investors can pattern-match

Repatriation of manufacturing (post-peak chip cycle, COVID)5

An energy and climate crisis

Better unit economics

Exponentially decreasing input costs and more developed tech primitives (AI models, commodity hardware, infrastructure-layer and outsourced advanced manufacturing companies)6

More talent (spin-outs from mafia companies and people moving from a bits world to an atoms one) means more staff and more companies founded7

Increasing willingness to experiment from core customers (e.g. DoD, NASA, Industrials)8

The net result of these is that its much easier to start a deep tech company now than it has ever been before. Funding aside, where previously I had to do everything in house, now I can outsource my manufacturing to Hadrian or Atomic Industries and pull a chunk of my ML models from Hugging Face’s libraries. Oliver Hsu put it well in Full Stack Startups in American Dynamism:

“In some cases, an early full-stack startup serves as the infrastructure that enables a new set of markets and companies pursuing them. A prominent example of this dynamic is in the commercial space industry, where SpaceX serves as the launch infrastructure for a number of other space companies, products, and services, making these businesses economically viable by de-risking getting to space. In these cases, the difficult work done by the full-stack startup enables new companies and markets by lowering technological and economic hurdles.”

Of course, all this is quite reflexive. The combination of lower costs of capital, and improved unit economics means more companies are being built. More companies should mean more money and more talent, and more talent should mean more companies again.

The impetus of this is hammered home by some of the strongest fiscal determination we’ve seen this side of the world wars. The ability of the state to pull monetary lever is structurally more constrained than it’s been in the last two decades, and the great problems of today – energy, climate change, defence, inequality, US dependence on production from China – all require enormous amount of state spending.

For what feels like the first time in 20 years we’re seeing the post-trough-of-disillusionment-early-inflection-point stuff happening in real world places.9

The Talent Problem

The elephant in the room is that there's likely too much money chasing too few founders. For the same reasons VCs have grown up in a world of bits, founders have too. It takes several years to train the requisite material science and hard tech innovation and most school programs are well behind.10

The road for talent is paved by breakout companies. When companies win they become prestigious places to work. This is especially true in a downturn when career risk turns top of mind and, outside of Tesla, we’ve yet to see a major public success story.11

Wall Street is venture capital’s main customer. Most of what we’ve sold them has been unprofitable garden-variety disappointment. Current sentiment has it that VC has, in the last decade, been a ZIRP phenomenon. So the result of rising rates? Less confidence in exits, lower private multiples, and devalued stock options. People want to work where there’s money and good vibes.

This is why the American Dynamism style narratives are so important - they bring a whole bunch of people into the heavier industries.

“Representation is an underrated force in human decision-making. The financial crisis was probably bad for the perception of financiers and kicked off the decline of the popularity of economics as a major for Harvard students. For most of the 2010s, the most visible figures in tech were Mark Zuckerberg and Jeff Bezos – software entrepreneurs par excellence.

The release of a movie about Zuckerberg seems to mark the inflection point in the popularity of Computer Science as a college major and the increase in applications to Y Combinator. Now the most famous person in tech (the world?) is Elon Musk, who is more closely identified with his deep tech companies like Tesla and SpaceX than with his software ventures, Zip2 and PayPal.”

- Matt Mandel, Four Theses on Deep Tech

Love, Death & Robots

We’ve found that much of deep tech has insufficient talent pools, or is either too CAPEX heavy for us. In the latter case, the value accrues to the deep pocketed Tier One who dilutes the smaller, earlier GP. We are looking for pockets of deep tech where this is now less true than it was, but most VCs haven’t realised this yet.

Some sectors have structural traits which mitigate dilution and allow for venture-scale outcomes. Sometimes it looks like now-cheaper primitives, or buckets of non-dilutive funding, or embracing business models which act as a wedge subsidising the earlier R&D milestones, and so on.12

Let’s take robotics as an example. Over the last five years, we’ve backed inter alia Terraform, Automata, and Compound who share this thesis:

The sector is de-risked

There’s very little scientific risk. We are taking market and tech risk

There’s ample follow-on capital13

It has improving business models

Advancements in compute, improved computer vision algorithms, and outsourced advanced hardware manufacturing have structurally reduced input costs, and makes higher-margin tasks automatable14

RaaS models facilitate a scalable way for companies to integrate robots into their operations without large upfront investments

Most teams were previously mechanical and systems integration engineers. They are increasingly software centric as the hardware is commoditised and software becomes the primary differentiator. The best founders are product-first and can sell into old industries without over-indexing on the tech.

It’s still tough to build and invest in well

Usually this is a combination of commodity hardware and sensors overlayed with software which adapts the robot to various tasks. This is a super technically hard problem

Unlike, say, semiconductors, it’s not a oligopolistic industry. These companies sell into old industries with fragmented buyers and face tougher regulation

Because of this, most investors we’ve spoken with overestimate the CAPEX required and the hardware difficulty, but underestimate the software complexity and the difficulty of integration

And there’s still a lot of upside

These industries are multi-billion dollar niches15

Most hardware robotics is a distribution for advanced software - think Apple or Nvidia owning the hardware and software stacks. Given enough time, these business models are wedges to replace human labour; the more intelligent they become the greater the costs they save16

In sum, why Deep Tech? Because it’s got improved unit economics broadly and a lower-than-historic cost of capital. The biggest constraint is still talent, though this is changing, and the are we like the most is robotics.

Why Is There A Bottleneck At Seed?

I mentioned earlier VCs are bits-people.

When it comes to deep tech, most outsiders are getting Founders Fund’s trash. Many we’ve spoken to don’t realise the extent to which insiders have known, built with, and passed on the deals they then see. They have neither the networks required to source or diligence these deals, nor the information asymmetry that lends itself to better picking.

Information asymmetry

The level of information and network asymmetry the top GPs carry is startling. Two, perhaps non-obvious traits of such GPs is a better understanding of commercial underwriting, and a gut-knowledge of what excellence looks like here.

Deep tech usually takes longer to inflect and the R&D costs and timeline are hard to underwrite. The sales cycles are very different to orthodox markets. Underwriting real commercial milestones, not just technical ones, is key.

“It no longer is believable that technology will sell itself, and it is more important than ever to be able to sequence to multiple commercial milestones (that lead to dollars on the balance sheet, not LOIs) in order to show step function changes of value accrual instead of technical milestones of years past.

This means startups must be better at scrutinizing the seriousness of potential early pilot customers and partnerships, while being ruthless in prioritization of the inevitable NRE that gets done for customers. In BD conversations, startups should be intimately aware of the collective buy-in of stakeholders instead of a singular Champion due to the unsteady economic environment.

In addition, more upfront conversations about payment will need to happen in order to both appease investors as well as minimize potential risk of disaster at the end of a long sales cycle. This will be a stark and uncomfortable change versus before when these were often left for later due to “unpaid/underpaid pilots with a promise to convert to higher dollar amounts” being enough for capital markets to get excited.”

Mike Dempsey, The End of Narrative Only Deep-Tech Companies

Underwriting excellence in a founder is something else we've seen outsider GPs struggle with. You need to have been in the room with greatness before to know what it looks like.17

You could take a high octane ex-Meta engineering manager who shipped like mad back in the day, but who fails because she can’t de-risk key tech risks before running out of money. Yes maybe she led Meta’s AI for X team but what did she ship? How demanding was she? Did she achieve a lot with very little? What does greatness look like in this context? Being able to articulate with structured granularity what non-obvious things make a great deep tech founder is something most GPs (outsider and insider) won’t be able to do.

Network asymmetry

A big chunk of the “our network adds value to startups” stuff is formulaic shilling of oneself. Where it actually does help though, is with sourcing, picking, and de-risking follow-on rounds.

Firstly, since most founders have pivot-preventing R&D and CAPEX spend, investors must be right on both the market and the tech. This requires knowing the handful of really good people really well in a given market. For instance, to underwrite a defence company you’ll need to underwrite the actual tech, the DoD’s needs, the various military involvements, and the competitive positioning between your company and the myriad others bidding for the same contracts. You can’t commoditise this type of government access.

Reading a couple Tegus sheets, calling a customer or a post-doc with a similar sounding PhD, chatting for 30 minutes, and figuring that you’ve done your weekly due diligence isn’t sufficient. Filtering what constitutes expertise is a skillset on it’s own. It takes years to build these relationships.

I enjoyed this take - around 12 minutes in - from Gil Dibner on this exact problem. His take, abridged: First, you need to ask “who is an expert in this field?” and filter for who to listen to (an incumbent, a professor, etc.). Second, you need to figure out how to filter what they say. It’s easy to find reasons why something won’t work. Putting the expert and the founder in a call together and watching the founder’s response to the arguments is helpful - most times you’re underwriting people anyway. There’ll be hundreds of unforeseen technical challenges for the team, regardless of what the experts say. If you assess technology, it’s easy to find an excuse. So the question isn’t “have they got it all figured out?” but rather “are these people uniquely capable of figuring it out?”. Are they defensive to challenges or they can stand their ground against these experts in a debate?

Secondly, follow-on relationships matter a lot. In the words of a friend building in the space: “to create another Anduril, one really needs to convince the Tier 1 defence VCs to jointly fall in love with a company so much they pump enough capital in it that it lives long enough to close the big deals”.

So, in short, why is there a bottleneck: because not enough GPs have the reps to pattern-match well and/or the expert network to source, diligence, and fundraise outstandingly.

A Very Long Shortlist

Below is a framing of some of the ways we’ll segment the GP market. Hopefully this doesn’t read too much like the thank you page of a dissertation.

First you have the big boys. Lux, Bedrock, Founders Fund, Khosla, SOSV, DCVC, 8VC, Eclipse, Prime Movers, Obvious, Innovation Endeavours and a16z are the big dogs in the yard. They provide multi-stage capital and have dedicated teams helping portfolio companies. Some of them (Seraphim, Fifth Wall, and Playground) specialise in one or more deep tech verticals. TenEleven, Paladin, Forgepoint, ClearSky, NightDragon are all multi-stage for cyber. There are other large generalists too, like Quiet, Canaan, Republic and Greylock who are increasingly investing here, but this is still a smaller portion of their portfolio. Many of the Tier 1’s will do sporadic deals but they’ve had a bit of a rocky start so far.

Then you have a whole swathe of sub-scale generalist VCs who also do deep tech. There are a ton here. Hummingbird, Angular, 1517, Long Journey, and Caffeinated, are some examples running fairly concentrated portfolios. GPs at Abstract, Asymmetry, Magnetic, Bee Partners, Boost, Outset, Julian Capital, Not Boring and Vine Ventures do the same.

The next layer is deep tech generalists. Compound (who have some great theses published), Cantos, and folk like Champion Hill, Root, 11.2, Shield, Wireframe, Elementum, Future Ventures and 50 Years are some of the more well known generalist brands at seed stage. They’ve all backed some of the more important companies to have come out in recent years.

F-St, Farpoint, Boom, Tamarack Global, Undeterred, AlsoCapital, Patty Wexler’s new firm Avila, Parkway, Silent Ventures, 2048, Bastion, FoundersX and Commodity Capital are some of the recent-funds-but-established-players in the space. There are roughly 83+ more GPs here I’ve not mentioned.

There’s been an unbundling of deep tech broadly. Many funds are now raised by specialists - though the scope for these is not always so clearly defined. Here are some of the more prominent ones:

Foundamental, Fifth Wall and Takeoff (construction tech)

Airbus, Space Capital, Type One and Space VC (space and aerospace)

Anorak, LDV and Earthling (VR/AR and visual tech)

Material Impact and Pangea (new materials)

Conviction, Hydrazine, Flying Fish, AIX, Cortical, Rackhouse, Lytical, Radical, Mythos, Pebblebed, Glasswing and Top Harvest and 40+ others (AI)

Riot, Countdown, Construct, Euclid and 81 Collective (industrials and “old industries”)

Cybernetix, Lemnos, Reinforced Ventures, Grep, Morado, Grit and Alley Robotics (robotics)

Harpoon, Decisive Point, Old Barracks, Razor’s Edge and Marque (all defence)

Heavybit, Amplify, Inner Loop, Surface, Essence, Sunflower, Preface, Ridgeline, Cervin, Work-bench, Array and Emergent and 59+ more (technical b2b infra)

First In, Ballistic, SYN, Runtime, LavRock, Squadra, Blu, New North, Rain, SNR, and Decibel (cyber)

Then there are a couple of generalist funds which are experimenting with what a venture fund should look like. Generational and Fundomo are unusually concentrated and the latter also invests part of the fund in lab-style teams. Rhapsody in the US and Deep Science Ventures in Europe both partner and co-build with entrepreneurs in a studio/venture fund hybrid. Applied Physics is working on a model to buy IP and tokenises the patents.

With hardware-first companies, there’s often a geographic localisation necessary. When a machine breaks down you have to go fix it in person. This creates more room than usual for an EU/US split in investors and most of the above are all the latter. BlueYard, Prima Materia, Lunar, Promus, Fly, VSquared, Spacewalk and Air Street, have been early backers of deep tech companies in Europe. Recent funds like Productive Capital, 2050 Capital, Entropy Industrial Ventures, 201 VC, and Positron are aiming to build the go-to EU deep tech seed firm.

In Israel, Entree, Cyberstarts, Gilot, and the teams at Hetz, Maple, and Meron cover a lot of complex software, while larger generalists like Aleph, and TLV will - if not doing Series A - occasionally lead rounds themselves at seed. Amiti and Symbol are both Israeli firms looking in fairly non-consensus segments of the market, Team8 and 10D do a stack of healthtech infrastructure, while UpWest, and Recursive target the highly technical Israeli diaspora.

Many universities will have their own hard tech innovation labs as well. MIT has The Engine and E14. Stanford has First Spark. Singularity University has Kitty Hawk, and now Caltech and Waterloo both have their own seed funds. There are a stack of spinoffs from the UK universities too

It may look like there’s a metric shedload of GPs here. There are, I’ve listed roughly 150. But there are around 5000 VCs globally. This is only 3% - there’s a lot of room for a whole lot more capital to ape in still.

An area where there seems to be a fair bit of whitespace is “Indian Dynamism”. This is a sector we are looking closely in to, so if you know anyone building or investing here, I’d love to chat to them. Some funds we’re aware of: Speciale Invest, BIF, Yournest, Pi Ventures and Navam have all recently backed some of the country’s emerging deep tech companies. The thesis is simply that India has emerging STEM talent, faces technologically competitive pressures from surrounding nations, and although it’s tried and failed in the past - there’s few enough GPs looking here that there needs only to be one or two major successes to return a good fund many times over.

This combination of looking for bottlenecks, tailwinds, and lack of GP competition is one framing of how we think LPs can approach investing in deep tech. Which leads us to our general framework of how to think about selecting GPs:

Smaller, early-stage funds have the most asymmetry

At seed information is murky, it is harder to distil signal from noise, networks matter more, and as valuations are lower you have the most amount of upside potential

Take high ownership and have concentrated portfolios

Unless you have Founders Fund top of funnel, you can only make a handful good decisions per year. The best tend to be an order of magnitude more selective than their peers

It is always better owning 1-2% more in an outlier than doing 1-2 incremental first tickets. The best take uncomfortably big bets when they have an edge

A huge indicator of GP success will be how they manage reserves and what they can do to make sure they’re doubling down on the right companies

Have a differentiated picking lens and look early in uncharted territories

Picking comes from hard-earned contextual insights

Most of these funds are emerging and don’t have several funds of track-record, so we only invest in funds where we can qualify their underlying portfolio or have some edge to vet their thinking against

All markets face arbitration. Investors must find an edge which carries them into places, crowds, and sectors where others aren’t looking. Most good investors have done this

What top 1% does not look like in deep tech

They invest in non-scalable components or target mid-market outcomes

They are one-legged stools: they are technical but lack the ability to underwrite founders, market, or product

They are overly niche, but have missed the best companies in that niche

They are low signal, high noise - they speak more to GPs than founders, index on their advisory committee, and write frequent thought leadership pieces on LinkedIn

Conclusion

Both LPs and GPs should have granular views on sectors they invest in - to the point where you can vet the other person’s thinking by virtue of having run the same thought trails yourself. The best LPs can underwrite the GP’s network and portfolios and benchmark the GP’s theses with their own. Nobody has a crystal ball, but there’s a familiarity with what constitutes thoughtfulness that’s pretty domain specific.

In some senses, it takes one to know one.

Summing up the above:

Despite the talent shortage, much of deep tech is benefitting from tailwinds resulting in a lower cost of capital and structurally better unit economics (for example, robotics)

Although this all looks pretty consensus, it doesn’t mean everyone will be able to invest here well

There is a bottleneck investing at earliest stages - there are high information and network barriers which great GPs can exploit

There’s a list of ±150 GPs who invest in deep tech; we look for ones with obscene selectivity, who double down on their best companies at the early stages, and who have a highly differentiated view of the world.

Of course, all considered, it’s also just cool to do cool stuff.

Elton Trueblood once wrote, “The major danger is not that we shall fail to appreciate past models, but that we shall lack the courage to be sufficiently bold in our creative dreaming….Whatever else may be the character of the redemptive society which the crisis of our time demands, it is at least clear that the society must make the habit of adventure central to its life.”

Thanks to Salar, Mike, Luke, and the many others who helped shape this piece. Appreciate you bucketloads.

Deep/frontier/emerging tech, whatever we call it. I’m excluding crypto, climate, and life sciences here. These require dedicated GPs. The latter will get it’s own blog post at some point.

Practically, I’m talking about robotics, advanced manufacturing, computation hardware, quantum, nuclear, energy storage, materials sciences, space, defence, and a handful of pure play software sectors like cybersecurity, AI/ML, devops, frontier enterprise or data infrastructure.

This ranges depending on who you speak to. Karthee has done a fair bit of research and landed at the average capital raised being $115m and 5.2 years to exit. Mike landed around 4-5 years from academia to first commercialisation and a couple others I’ve chatted with at the 8 ish year marks to exit. CB Insights unicorns-list link.

Some sub-sectors (like quantum, fusion and neuroscience) are still comparatively fringe and haven’t seen the recycling of talent or pioneering companies yet. Others (chip design, space launch, transportation, defence hardware) are usually either a sight more competitive or have too large dilution profiles. There’s work from BCG outlining which verticals are appealing to corporates and which are fastest and cheapest to commercialise. The TL;DR: advanced materials, orthodox biotech, and photonics & electronics take the longest to commercialise and will be the most dilutive.

We first noticed this shift happening in life sciences back in 2018 around the time of our first investment into BillionToOne. Back in the day, the average life science founder was a hired gun, they accept the binary outcome of drug failure and hope for a reasonable exit. Not a great one, but a reasonable one. Founders like Oguzhan (BillionToOne) were a rarity - they prioritised the tech over the bio and built for scalable platforms from day one. They were also building with $10bn+ outcomes in mind.

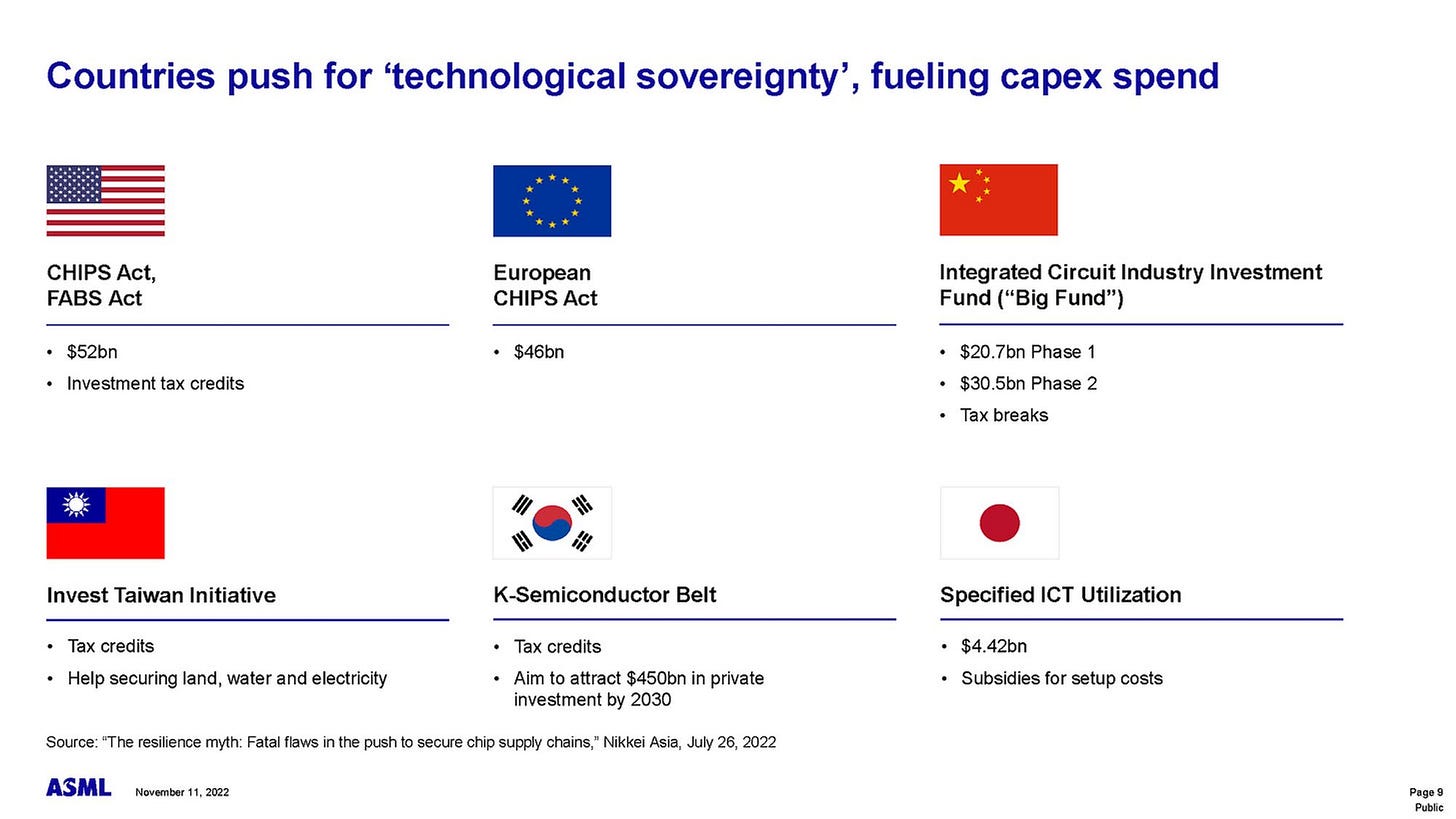

The combination of Sino-US tensions, a post-peak chip cycle, and COVID has brought the shortcomings of globalism to the front of everyone’s minds. There are now a ton of state subsidies. The picture below (ASML with h/t to dylan) underestimates the Chinese investment into semiconductors by an order of magnitude.

In the middle of last year the US passed USIC Act - a $280bn bill for investment into semis, AI, robotics and quantum. China has been pushing this agenda for a while, most heavily in their recent 5-Year Plan.

DARPA care a lot about supply chain resiliency. This summary paper of ~half the DARPA research programs contains 11 mentions of “supply chain”. Also the American Industrial Dynamism wiki and library have extensive content on repatriation dynamics. Operation Warp Speed was a tremendously successful example of this, helping Moderna bring vaccines to market at a ridiculous pace. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6

To quote Matt: “Other elements of the COVID response have similarly unlocked funding for deep tech companies, like the American Rescue Plan’s loan guarantee program for companies working on food supply chain resilience. Before COVID, the 2017 tax bill created the opportunity zone program, incentivizing tangible investments in distressed American communities, and Obama-era Energy Department loan guarantees helped Tesla go on to become one of the most valuable companies in the world.”

Post SpaceX’s breaking of the industrial oligopoly, folk like Hadrian, Varda, Blue Origin, et. al. are all now selling into previously closed customers. Some more essays on increasing willingness to source from startups: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6

In 2019, the DoD created a new branch of the military, The Space Force. The last time that happened was the creation of the Air Force in 1947. The initial budget for the Air Force was $5.5 billion in 1947 and grew to $216.0B in 2023. The initial budget for the Space Force was $15.4B in 2020 and grew to $26.0B in 2023

Regarding the debate on physical stagnation and today’s inflection points: I recommend reading Rise and Fall of American Growth by Gordon, and Vanguard’s research on the “idea multiplier” to frame this further. Here’s a podcast with Meb Faber if you’re lazy. Some tie progress/stagnation to monetary policy, others segment it by field. TL;DR is it’s super debated whether we’re stagnating or not and mostly comes down to semantics on measurement (here’s a literature review).

It’s a little trite to say, but a lot of what was hot in the tech world over the last couple of years did not have enduring economics (companies like SWVL, Bird, and a ton of CPG businesses). Looking into public market 10 baggers, most of the outperformers in public markets from last two decades have actually been companies that lean into cap-ex to create value.

Within the US, for every one kid studying engineering or life sciences, there are roughly nine who are studying something different, and roughly another ten who are not studying at all.

In some verticals (like transportation, space, AI, and defence) executive talent is being spun out of breakout companies (e.g. Tesla, NIO, SpaceX, Anduril, UiPath, Celonis, Shield AI). But there have been precious few of these in the likes of quantum (PsiQuantum?), new materials, semiconductors (NextSilicon?) or construction.

The best way to put a lid on CAPEX spend is by hiring. Having a team which can ship product improvement quickly, cheaply, and at minimal failure rates is key. We’ve found the difficulty of this is under-appreciated by most investors - there’s just not that many great product folk in hard tech. Managing a production line is a core capability on it’s own and hiring folk who can do this well, while selling into companies much larger and slower than them, without sacrificing clockspeed is one of the tougher challenges founder’s face.

So far in 2023, roughly 60% of the number of rounds and >75% of the funding went into rounds post Series A. Generalist brand names like Tiger, Sequoia, and a16z are actively making bets here.

For example, a brick-laying company selling into The Netherlands, UK, Germany, Poland and France would have a conservative TAM of $12bn assuming ±600k new homes per year and a low end of $20k revenue per unit.

You capture the real world data from sensors, feed it into a broader system, improve the dataset you use to train the robot, and allow the entire system to make smarter decisions. This approach can wedge into full workflow integration and make room for yet-to-come hardware and software improvements

Roughly 75% of deep tech unicorn founders have 4+ years of niche industry experience and 73% (depending how you measure it) are based outside of SF and closer to customer bases. Most GPs simply don’t have this history and aren’t in go-for-drinks vicinity with founders here.